Welcome to Mystic Mondays, where the veil is thin, the habits are strange, and the weirdness is holy. 🔥

(P.S. Sorry for putting out a Mystic Monday out on a Tuesday but yesterday was Memorial Day and my children were home…)

Last week, I wrote about Hildegard of Bingen’s visions and her place as a feminist icon. This week, we’re talking about languages.

Or rather, one “unknown” language.

A Secret Vice

Most languages develop naturally over centuries.

But invented languages are created for a variety of purposes. They can be used to study the way languages work. They can help groups to communicate if they don’t speak the same native tongue. For example, Esperanto is the world’s most widely spoken constructed auxiliary international language. It is used to help international groups communicate.

And then there are languages invented for artistic purposes or to enhance a fictional story, like the languages constructed for Star Trek or Ursula LeGuin’s fantasy worlds.

The term for someone who creates languages is glossopeist1.

The king of invented languages is, of course, J.R.R. Tolkien. He constructed more than a dozen languages for the world of Middle Earth. But Tolkien saw his language invention as very personal. In his essay “A Secret Vice,” he describes this dedication to language invention tentatively, almost as “private, obsessive, and slightly embarrassing—a secret vice.”2

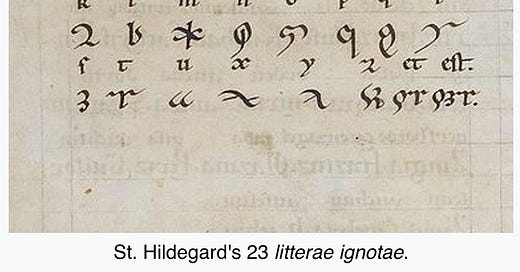

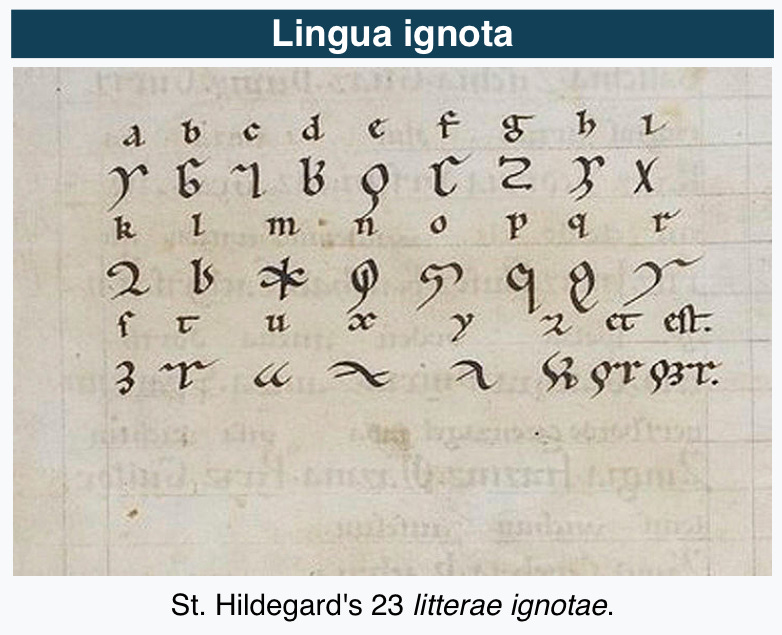

Lingua Ignota

Language invention was not a secret vice for Hildegard of Bingen, at least not later in her life when she offered it as justification for her authority to give counsel to a Pope.

Hildegard created a language referred to as Lingua Ignota, or unknown language.

The words that we have from her invented language are mostly nouns. That didn’t mean there weren’t other words in her Lingua Ignota, like verbs, but they haven’t survived.

There are theories about the purpose of her language.

Was it for the nuns to whisper gossip to each other about a visiting bishop? Was it a language used for sacred purposes in the Divine Office? Or was something else?

Hildegard’s friend, confessor and scribe, the monk Volmar wrote a few years before her death, “Where then will the voice of your unheard language be?” Did he expect this language to be used more widely?

“When a woman invents language, antennas are raised.”

Early scholars were quick to downplay Hildegard’s Lingua Ignota as a kind of glossolalia, or speaking in tongues, and therefore not a serious language but “an ecstatic language associated with ‘hysterics’”

In her translation Hildegard’s Lingua Ignota, Sarah Higley, who is a glossopoeist herself, believes that Hildegard’s language was “a linguistic distillation of the philosophy expressed in her three prophetic books: it represents the cosmos of divine and human creation and the sins that flesh is heir to.”

In other words, Hildegard’s Lingua Ignota is not a result of spontaneous religious fervor (though there is a place for that). Instead, it is another way Hildegard intentionally communicates her remarkable theological output and her vision for the world.

Through various mediums, Hildegard found ways of expressing her vision of creation and the call she had heard from God. After much pain and angst, she finally wrote down her visions. She then commissioned images of these visions. She explained those visions theologically. She composed music. And then she went ahead and invented a language. All in the service of communicating that call.

Hildegard defies the expectations of all of the ways in which we might label her: woman, nun, chronically ill person. Her response to her place as a religious woman in a patriarchal hierarchy is to offer an array of rich and remarkable words that not only defy categorization but confront the things she views as corrupt in the world.

Letter to a Pope

In a letter in 1153 to Pope Anastasius, Hildegard wrote:

“O man, the eye of your discernment weakens; you are becoming weary, too tired to restrain the arrogant boastfulness of people to whom you have trusted your heart…You are neglecting justice, the King’s daughter, the heavenly bride, the woman who was entrusted to you.”

She continues with the proof of her own right to call him out:

But he who is great without limit has in our time touched a small tent {Hildegard} so that it might behold wonders, fashion unknown letters, and let an unknown language be heard. And it was said to this little tent, “What you express in the language announced to you from above will not be in the ordinary human forces of expression…”

She ends the letter with this bold but hopeful rebuke to the Pope:

“And so, O man, stand upon the right way and God will rescue you. God will lead you back to the fold of blessing and election and you will live forever.”

May we all be so bold in the face of power.

Listen to a few words of Hildegard’s Lingua Ignota sung by Barbara Hannigan.

If you like what you’re reading, I’d appreciate it if you shared this post, subscribed, or left a comment. Even just tapping the cute little “heart” button at the bottom to show you resonated. Thanks for hanging out in this space!

The world of contemporary glossopoeists and their conlangs, or constructed languages, is fascinating.

All quotes are from Sarah Higley’s Hildegard of Bingen’s Unknown Language except the final letter to Pope Anastasius. This is from Hildegard of Bingen’s Book of Divine Works, edited by Matthew Fox.