Orpheus…could move stones and wolves with his music, but Christ, the New Song…has turned stony minds and wolvish hearts into men. It is he who created the cosmos and the microcosm and ‘makes melody to God on this instrument of many tones…A beautiful breathing, instrument of music the Lord made man, after His own image. He Himself…the celestial Word, is the all-harmonious, melodious, holy instrument of God.2

This is a quote from Barbara Newman’s Saint Hildegard of Bingen: Symphonia of the Harmony of Celestial Revelations, the name of Hildegard of Bingen’s ordered collection of songs and compositions.3

Newman quotes the 2nd century theologian Clement of Alexandria but she is also exploring Hildegard of Bingen’s theology of music and its importance to God and creation.

Hildegard produced an extensive range of writing in a wide array of subjects: her visions from heaven, celestial music, a dramatic play, tomes for healing cures, and hundreds of letters to people as varied as popes, the emperor, and a local monk or nun. In most of her writing, she made a startling claim: that she was both a lowly woman and the mouthpiece of God.

‘untaught by anyone, I composed and chanted plainsong in praise of God and the saints, although I had never studied either musical notation or any kind of singing.’

Hildegard’s theology of music was mystical. She believed that “the very soul is symphonic,” a view not so strange for her time. The ancients, and later the medieval world, believed that the universe was ordered into three kinds of music4:

Musica universalis or the music of the spheres—the music made by the planets and stars

Musica humana—the harmony that binds the parts of the human together, body, soul, and spirit

Musica instrumentalis—man-made music, any instrument including the human voice

Later, religious folk would add on Musica celestis—the music made by God and God’s heavenly beings

Hildegard’s music emerged from an ethos that concluded that music was so powerful, with the power to heal and inspire or to damage and break, that making “dangerous music was immoral” and “to be immoral was to be unmusical.”

This didn’t mean that if you’re tone deaf, you were evil. After all, the music of the spheres was inaudible to humans (or at least we were so used to it that it didn’t register in our ears anymore).

What it did mean was that the universe, as created by God, was so full of God’s harmonies that to go against them made one dissonant with God. In this vein, angels were “pure spirit and therefore pure song” and the devil was “the ultimate unmusical spirit.”

In much of her theology of music, Hildegard is echoing both the ancients and her contemporaries but she adds her own contribution when she writes about Adam and the fall. Before the fall, humans were in melodious harmony with God. Music was “quintessentially human; mankind was never meant to live without it.”

The one who came to save humans after the fall was Christ, the “musician, minstrel, lord of the dance,” or as Clement of Alexandria wrote, “the New Song…the all-harmonious, melodious, holy instrument of God.”

Where some of her contemporaries (as well as earlier theologians like Augustine) prized the words of music over the melody (and in fact, they worried that music could not only distract from the words/meaning but it could also be destructive and dangerous), Hildegard wasn’t worried about that.

She saw melody and liturgical song, in particular, as the medium through which the parts of the human being could be united in the way that Christ united the divine and the human in himself.

This way of seeing the cosmos as musical fell out of favor for a while, disproven (or so was thought) by later scientists and philosophers.

But more recently, astronomers and other scientists have seen a connection between the mathematical order of the universe and the music of the cosmos. Space exploration has discovered ‘sounds’ in space, “plasma waves ripple between Saturn and its icy moon Enceladus, the gas giant Jupiter cracks and booms constantly with lightning bolts and thunder.”

Nobel Physics Laureate George Smoot III commented that if “‘the universe is, at some level, music, then it seems only natural that we should study it with musical tools of thinking.’”6

Perhaps the ancients had a point.

For Hildegard, “all music was associated with prophecy and the nostalgia for Eden.”That’s why, she noted, we can have an emotional and physical response to the nostalgia of certain melodies. Our created selves recall the time before, when we were attuned to the “celestial harmony” of Eden.

What if we saw all creation and all creatures as musical? Would it change the way we treated the earth if we believed that our destructive tendencies interrupted the harmonies that God spun out into the cosmos?

Does it seem that some of our national and world leaders have lost the melody of the heavens? Would it change how we treated others if we remembered that each of us were made, like Adam, to sing “the sound of every harmony and the sweetness of the whole art of music?”

Listen to a recording of some of Hildegard’s music and let me know what you think.

Books I’ve been reading (and loved):

Everything Sad is Untrue by Daniel Nayeri

Emily Wilde’s Encyclopedia of Faeiries trilogy by Heather Fawcett

Tress of the Emerald Sea by Brandon Sanderson

Hildegard of Bingen: Scivias, translated by Mother Columba Hart and Jane Bishop

Miscellaneous things I’m into lately:

No Write Way, a podcast by a writer, interviewing writers to tell writers everywhere that there’s no one way to be a writer.

This conversation between artists Mako Fujimura and Lee Camp on the podcast No Small Endeavor was so touching. It made me want to go and make art of all kinds.

The Injustice Report to get smart updates about the Trump administration’s policies

The soundtrack to the movie Mufasa. Lin Manuel Miranda has done it again.

My friends’ bookstores. We’ve been trying hard to wean ourselves off of Amazon so we use the library, try to find used books at abebooks.com, or support local bookstores. Try True Leaves bookstore in Illinois or Nooks in Lancaster, PA.

I think this image is from a 1910 postcard but I’m linking to this website in case I’m not crediting the artist correctly: https://www.album-online.com/detail/en/MTI0YjQxMA/hildegard-von-bingen-mystic-bermersheim-1098-kloster-rupertsberg-convent-1179-alb5705603#

Emphasis is mine here.

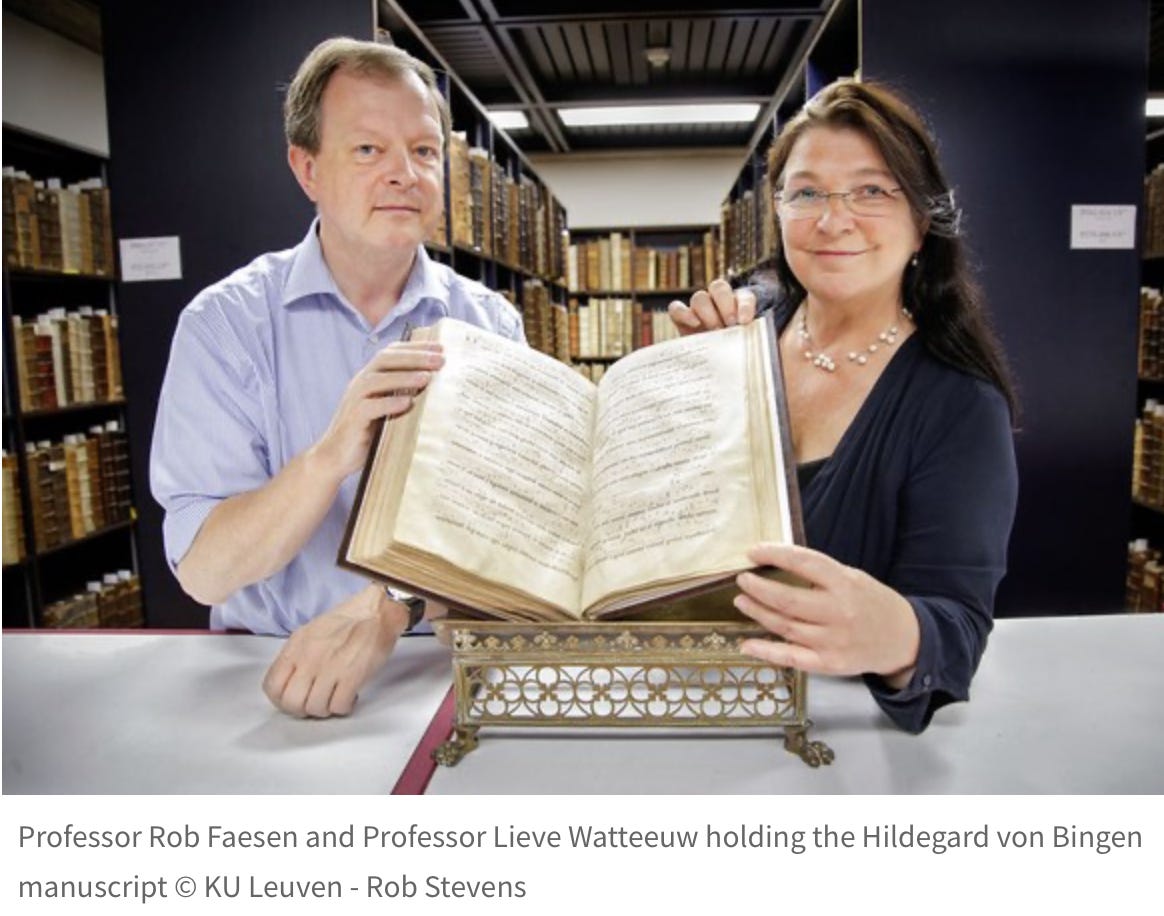

There are two original versions of Symphonia. One was a draft that Hildegard sent to the monks at Villers Abbey in Belgium (then known as the Low Countries) in 1147 after her fame began to grow and they wrote letters asking for wisdom from this visionary. The other was compiled after her death.

All of these quotes and much of this history is from Barbara Newman’s Saint Hildegard of Bingen: Symphonia, Cornell University, 1988.

This photo is from Leuven news which reported their acquisition of Hildegard of Bingen’s Dendermonde Codex, the draft of Symphonia that she sent to Villers Abbey in 1147. The ruins of Villers Abbey are close to Leuven, Belgium.

https://www.auroraorchestra.com/2019/05/pythagoras-the-music-of-the-spheres/